Utilization of Date Tree Leaves Biomass for the Removal of Heavy Metals from Water

Journal of Engineering Research and Sciences, Volume 1, Issue 4, Page # 137-147, 2022; DOI: 10.55708/js0104016

Keywords: Heavy Metals, Date Tree, Adsorbent, Activated Carbon, Metal Oxide

(This article belongs to the Section Chemical Engineering (CHE))

Export Citations

Cite

Silas, K. , Ngulde, A. B. and Mohammed, H. D. (2022). Utilization of Date Tree Leaves Biomass for the Removal of Heavy Metals from Water. Journal of Engineering Research and Sciences, 1(4), 137–147. https://doi.org/10.55708/js0104016

Kiman Silas, Aliyu B. Ngulde and Habiba D. Mohammed. "Utilization of Date Tree Leaves Biomass for the Removal of Heavy Metals from Water." Journal of Engineering Research and Sciences 1, no. 4 (April 2022): 137–147. https://doi.org/10.55708/js0104016

K. Silas, A.B. Ngulde and H.D. Mohammed, "Utilization of Date Tree Leaves Biomass for the Removal of Heavy Metals from Water," Journal of Engineering Research and Sciences, vol. 1, no. 4, pp. 137–147, Apr. 2022, doi: 10.55708/js0104016.

Cadmium (Cd) is known to have adverse effects on the kidney, liver, bones and cardio-pulmonary system, this heavy metal is usually consumed from drinking water with higher Cd acceptable limits. In this study, Activated Carbon (AC) is produced from Date Tree Leaf (DTL) and impregnated with Zinc Oxide catalyst, where an adsorbent (ZnO/DTL) was developed and used in the adsorption of heavy metals from water samples from three areas of Maiduguri, Nigeria where there are reported kidney problems caused by Cd. The highest concentration of Cd from Dala Kwanan Osi is of Maiduguri (0.017 mg/l) is observed to be completely remove even less than the maximum permitted limits of 0.003 mg/l. The outcomes from SEM, EDXRF, FTIR spectra and XRD patterns revealed the characteristics of the adsorbents. Also, the isotherm study indicated that Langmuir isotherm supersedes (0.9684) the characteristics shown by Freundlich isotherm (0.8479) hence it is more suitable to explicate the correlation of experimental results. It is proven for the first time in Maiduguri, Nigeria that the DTL can now be considered as a waste-to-wealth commodity suitable for the cheap and simple means of removing Cd contamination and other heavy metals from borehole water.

1. Introduction

Water is a very basic source for the existence of life on earth however, the increase in industrialization and modernization has contributed negatively to clean water resources. Many substances such as heavy metals, dyes, pharmaceuticals, surfactants, pesticides, personal care products, and others have contaminated the water resources [1]. These pollutants are environmentally hazardous to human beings and animals [2]. The excess quantity of heavy metals in water causes irritation of the central nervous system and damage to the kidney and liver, Lead (Pb) and Cadmium (Cd) are the most toxic heavy metals which cause many diseases [2,3].

Biomass is abundantly available from several sources all over the world and has numerous roles to play in sustainable development. In addition, to being a food source and renewable raw material, biomass can be used for energy production, carbon sequestration, and as an essential element to produce biochars and activated carbon [4,5].

The conventional technologies for heavy metal contaminated water are precipitation, electrochemical treatment, ion exchange, membrane separation, and adsorption. However, adsorption has been proven to be one of the most suitable and universal methods, which offers remarkable advantages such as fast water treatment, ease of operation, availability, and efficiency [6]. Various adsorbents have been employed in adsorption, ranging from natural products to synthetic materials, carbon materials, such as activated carbon, graphene, and fullerene, were found to be promising adsorbents for removing heavy metals from aqueous solutions due to their stability and large surface area [6-7]. Date Palm fibers are lignocellulosic materials that consist of three vital components: Cellulose (40-50 %), hemicellulose (20-35 %) and lignin (15-35 %) [8] and may be used as adsorbent to remove heavy metal ion from water.

Each date palm tree produces 20 kg of dry leaves yearly [9] while the area under date palm cultivation in Nigeria was estimated at over 1,466.00 ha with an annual production of nearly 20,000 tons of date fruit per annum [10]. The Date Tree Leaves (DTL) stems and branches are waste and are being burnt while in most cases, they are thrown to liter the environment to become the part of teaming solid waste. As of now, there are no sustainable long-term management strategies to utilize the DTL towards an economical and practical approach to environmental cleanup however, other study [11] reported that AC produced from waste biomass can be utilized to that effect.

AC can be used as a support of Metal Oxides (MO) in the adsorption of heavy metals and are impregnated on the AC as an active catalyst phase due to their low production cost [12]. Wheat Straw Biochar (WSB) was activated for cadmium removal from contaminated water, they found that WSB is a cost-effective and environmentally friendly strategy for the removal of metals from contaminated water [13] however, there is no detailed adsorption time study that is expected to be high due absence of a catalyst. A review on the removal of Cd(II) and other heavy metal ions from aqueous solution by Zinc Oxide (ZnO) nanoparticles as adsorbent was reported [14] however, the shortfall of unsupported MO catalyst involves high cost. The ZnO/activated carbon adsorption capacity (96 mg/g) for the adsorption of Cd2+ ions was reported [15] but AC is expensive, therefore, there is a need for developing AC from a cheap local source. Many studies of the removal of heavy metals from contaminated water using AC/MO can be found in the literature [16]–[18]. Hence, ZnO is cheap, and be easily synthesized with AC.

The objective of this work is to produce Activated Carbon using DTL and to impregnate the AC with Metal Oxide (ZnO) also, to characterize the adsorbents before and after adsorption by FTIR, XRD, SEM, EDXRF techniques. The developed adsorbent (ZnO/DTL) will be used to remove heavy metals from three water samples obtained from some areas in Maiduguri, Nigeria. Furthermore, the adsorption isotherms based on Langmuir and Freundlich will be used for the description of the adsorption of the heavy metals over the adsorbents.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Material

Zinc Oxide (ZnO), Hydrochloric acid (HCL) and deionized water were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. All the chemicals and reagents used were of analytical reagent (AR) grade or as specified.

2.2. Adsorbent preparation and impregnation

The DTL were collected from a date palm plantation in Moduganari, Maiduguri, Nigeria. the collected leaves were crushed to smaller particle size and washed with distilled water several times to remove dirt particles and water-soluble materials. The washing process is continued until the wash water contained no color. The washed material is then dried in an oven at 50 OC for 24 h. The sample obtained from the pretreatment process above was then heated in furnace at 600 OC for 1h and left in the furnace for 24 h to cool in the absence of oxygen. The result obtained from this process is the carbonized sample otherwise known as the Non-impregnated Date Tree Leaves (NIDTL) adsorbent as used in this work. The NIDTL adsorbent produced was activated in accordance to the literature [19] to obtain an activated carbon material Non-impregnated Date Tree Leaves Activated Carbon (NIDTLAC). Further, the NIDTLAC is impregnated with an appropriate aqueous solution of ZnO to develop ZnO/DTLAC adsorbent. The impregnation is simple and easy to carry out [12] unlike other synthesis methods which require specialized equipment such as microscopic/spectroscopic technique as explained in another study [15].

The adsorbent was heated with constant stirring at 70 OC and 300 rpm until the entire liquid is evaporated and then dried at 110 OC for 24 h. After which the obtained samples were later calcinated at 400 OC for 2 h to bind the ZnO catalyst to the AC surface.

2.3 Adsorption activity

The water sample collected from the wash borehole in Maiduguri is analyzed via Atomic Adsorption Spectroscopy (AAS) to detect the presence of arsenic, cadmium, chromium, copper, and lead. After the adsorption, water sample is tested again to check the reduction/ removal of heavy metal initially present in the water sample. water samples collected at three different borehole water points within Maiduguri metropolis.

2.4. Characterization techniques

The characterization of the samples was carried out with; SEM analysis (JSM-6010LA, JEOL, Japan); XRF analysis (X-ray Fluorescence Spectrometer-EDX7000, SHIMADZU Corporation, Japan; FTIR spectra, Bruker Alpha infrared spectrophotometer) with a resolution of 4 cm−1 (range 400–4000 cm−1); XRD analysis (BRUKER X-ray Diffraction).

3. Results

3.1. SEM morphology

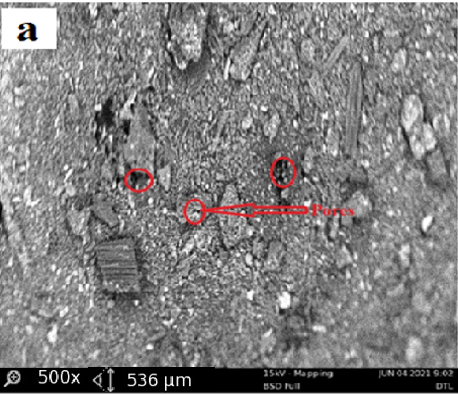

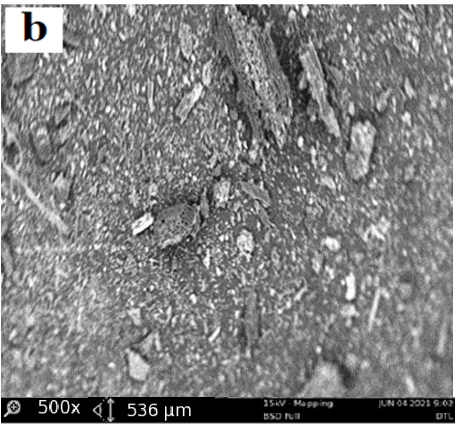

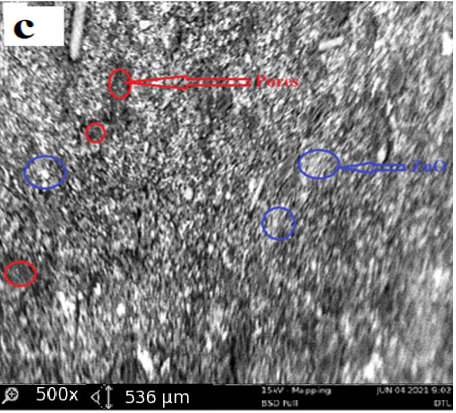

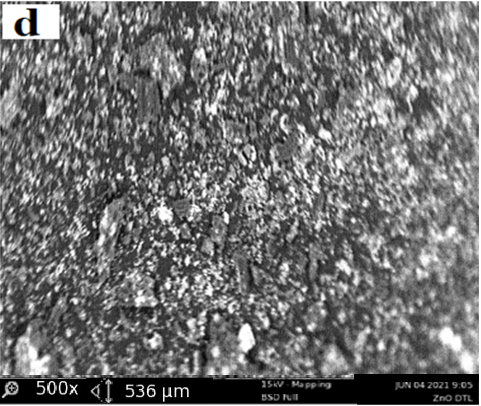

The structural properties of activated carbon are effective at adsorption capacity, also the interactions of adsorbate/adsorbent play an important role in the adsorption process however, the improvements of the activated carbon properties is realized by impregnating the ZnO over its surface. The ZnO/DTLAC shows that the morphology contains many pores and caves, which may be due to ZnO evaporation during the carbonization step, similar finding has been reported [11]. The surface of the adsorbents is rough with particles and with amorphous nature of carbon in accordance with previous researchers [20]. Large blocks containing regular channel arrays can be observed with larger pores, this can indicate that the DTLAC preserved the original structure, even after calcination these pores can facilitate the diffusion of the organic molecules inside the composite. This observation was found to favorably agree with other study [21]. Previous SEM analysis after surface modification, showed that the surface structure remained porous with ZnO nanoparticles [22]. The morphology of the ZnO/ DTLAC and NIDTLAC adsorbents are shown in Figure 1.

Also, there are visible pores on the adsorbent that necessitate the adsorption to occur, similar morphological structure can be seen for all the adsorbents. Large blocks containing regular channel arrays can be observed with larger pores, this can indicate that the DTLAC preserved the original structure even after calcination.

Furthermore, the porous nature of DTLAC can be seen to have provided a more possibility of additional loading space for ZnO nanoparticles, this agrees with a study [23]. Figure 1 showed many white spots distributed over the surface of DTLAC, confirming the presence of ZnO nanoparticles, reported similar morphological study can be found in the literature [11,21]. Also, the SEM images of TiO2/kaolinite nanocomposite is presented [24] that shows the white spots of TiO2.

The outcomes of the current SEM images demonstrated that after the heavy metal removal, the surface became relatively smooth however with visible pores and white spots of nanoparticles which suggests that occupation of the adsorbent sites by the adsorbates are partial and there is room for further adsorption activity. From the discussions, an evident change occurred for the morphology of ZnO/DTLAC and NIDTLAC adsorbents before and after adsorption. The same behavior of morphological transformation has been revealed previously [25].

3.2. Elemental analysis

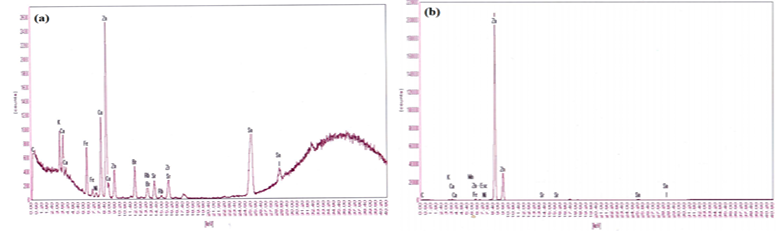

Characterization of EDXRF shows the chemical composition of the adsorbent which indicates the formation of nanocomposites for ZnO/DTLAC with the visible presents of Zn on the spectra while there is none of these metal oxides on NIDTLAC adsorbent since it is not impregnated with any of the metal oxide, similar XRF result previously can be found elsewhere [26]. Figure 2 shows the EDRF spectrum.

The EDXRF spectra show also that the higher peaks correspond to a greater quantity of the corresponding element in the sample [27]. Table 1 shows the EDXRF elemental analysis.

Table 1: EDXRF Elemental Analysis

Element | ZnO/DTLAC (%) before adsorption | ZnO/DTLAC (%) after adsorption | NIDTLAC |

Zn | 37.167 | 27.876 | 0.5608 |

Cu | – | – | 0.3243 |

Sn | 8.586 | 9.458 | 16.512 |

Cd | 0 | -0 | 0 |

LOI | 32.49 | 41.74 | 68.15 |

LOI=Loss in ignition by EDXRF spectroscopy

The importance of the knowledge of the LOI can also be employed as an indicator in monitoring the quality of the final product, it is the amount of weight loss through raising the temperature of the material to a predetermined level [28]. Many studies showed the loss on ignition by EDXRF spectroscopy [29-31]. Characterization of the ZnO/activated carbon nanocomposites in Cd sequestration was reported [15] for FTIR, SEM and XRD without elemental study. It is observed that the intensity peaks of Zn with respect to the other elements is higher for ZnO/DTLAC while the other elements are in very low quantities, so they are not significant for the composition of materials. This finding agrees with a literature [32] however, Sn is also a major element in the composition of DTL and can be seen to be present in all the samples. The amount of Zn reduces after the adsorption which can be attributed to the blockage of Zn nanoparticles dispersed on the DTLAC by the adsorbed heavy metals. The Cd element in the water sample is totally adsorbed and due to its minor amount, it does not show in the peaks of the adsorbents after adsorption. Loss on ignition value of the adsorbents are high indicates high carbonaceous matter [31].

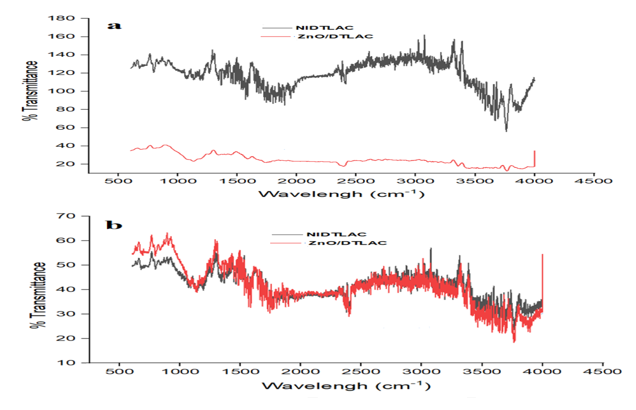

3.3. FTIR analysis

The peak position on the spectra illustrates the presence of a certain functional group with the form of vibration it exhibited. Figure 3 shows the FTIR spectra of NIDTLAC and ZnO/DTLAC adsorbents.

and (b) after adsorption

The shifting of peaks to higher wavenumber and appearance of new peaks showed successful adsorption of the heavy metals [33] and may be due to the interaction of the heavy metals with the functional group [34]. The absorption band at 1578 cm-1 arising from aromatic group (C-C), is indicating the formation of carbonaceous material [31]. Table 2 shows the functional groups on the FTIR peak positions and their vibration forms.

Table 2: Functional groups on the FTIR peak positions and their vibration forms

Peak position (cm−1) | Functional groups | Vibration form | Reference |

38062a 3864b | ―OH and―NH | Stretching vibrations | [35-37] |

3761a 3763b 3768c,d 3870c,d 3358 c, d 3355 d 3431d | O―H | Stretching vibrations | [36-37] |

3271b | C–O | stretching vibrations | [38] |

3036b,d 3133d

| O―H | Stretching vibrations | [39] |

2905b | C -H | stretching vibration | [33] |

2838a 2840b 2713c,d 2830c,d | C-H | stretching vibrations | [39] |

1951a,d 1959b | C–C | Stretching | [40] |

1568 a,b,c,d 1584 c 1574 d | C-C | Stretching | [31] |

1197a 1186b | C–N | Stretching | [34] |

694a,b | C − H | bending vibration | [39] |

687 c | Si–O | Stretching and bending vibrations | [41-42] |

aFTIR peak of NIDTLAC before absorption, bFTIR spectrum of NIDTLAC after adsorption cFTIR spectrum of ZnO/DTLAC before absorption, dFTIR spectrum of ZnO/DTLAC after adsorption

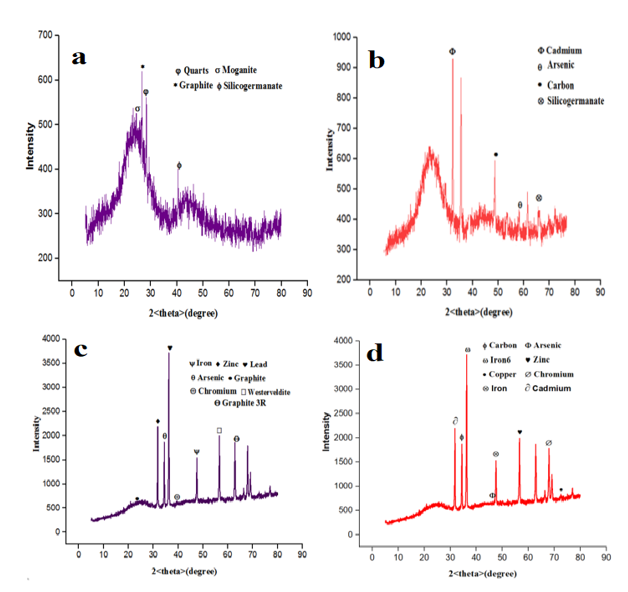

3.4. XRD minerology

The XRD patterns show the diffraction peaks of several phases according to the non-impregnated date tree leaf activated carbon adsorbent. Again, the activated carbon pattern showed an amorphous halo centered at 2θ = 23O, which is refers to the reflection of the plane (002) [43], a common feature of non-crystalline structures such as activated carbon. The plane (002) corresponding to activated carbon is confirmed in other studies [39,44]. XRD pattern shows the diffraction peaks of many phases. It indicates the type of XRD peaks belonging to amorphous structure of activated carbon changes into some degree of crystalline nature, previous research shows similar trend [11,45]. Figure 4 shows the XRD analysis of the adsorbents which NIDTLAC showed a highly amorphous nature of the adsorbent in absence of any of the heavy metals, similar conclusion was reported [42]. The intense (100), (002), and (110) peaks can be ascribed to crystalline ZnO with the hexagonal structure (JCPDS card No. 36-1451) [46].

This study suggests an increasing of crystallinity for ZnO/DTLAC adsorbent attributed to the much lower DTLAC amount when compared to the NIDTLAC and same pattern was observed [43]. The phases are presented in Table 3 for the adsorbents.

The change in chemical composition of the adsorbent after adsorption occurred due to the catalyst activity. At the XRD peaks, Cd and Cr appeared at 2θ= 36.4 and 58.7O respectively. The ability of the adsorbent to remove the metals from water is depicted by the present of those metal on the diffraction peaks and the corresponding absence of the metals in the AAS analysis after adsorption. The result indicated that Cd and Cr are attached onto ZnO/DTLAC adsorbent after adsorption furthermore, the XRD spectra with the presence of Cd and other heavy metals indicated the formation of partially amorphous solids [42,47]. The study of activated carbons adsorption of heavy metals [48] showed the present of elements and not compounds on the XRD diffractions also, in this study there is no obvious single compound on the XRD diffraction.

3.5. Water Analysis

The source of Cd is from the drinking water (0.017 mg/l) at Dala kwanan Osi while the maximum consumable amount is 0.003 mg/l. Table 4 shows the AAS analysis results before the adsorption of the heavy metals.

Table 3: Phases, Chemical Formulae and Quantifications of Adsorbent Before and After Adsorption

Before Adsorption | Chemical Formula | After Adsorption | Chemical Formula/ (%) |

NIDTLAC | |||

Graphite | C6.00 (20.2) | Cadmium | Cd2.00 (2.4) |

Quartz | Si3.00 O6.00 (7.1) | Silicogermanate | Si152.00 O304.00 (50.1) |

Moganite | Si12.00 O24.00 (14.1) | Arsenic | As6.00 (3.5) |

Silicogermanate | Si152.00 O304.00 (58.6) | Carbon | C16.00 (44) |

ZnO/DTLC | |||

Zinc | Zn2.00 (3) | Cadmium | Cd2.00 (6) |

Graphite | C16.00 (8.1) | Zinc | Zn2.00 (21) |

Chromium | Cr2.00 (3) | Chromium | Cr2.00 (7) |

Iron | Fe2.00 (1) | Copper | Cu4.00 (1) |

Westerveldite | Fe4.00 As4.00 (1) | Iron | Fe2.00 (1) |

Graphite 3R | C6.00V(79.8) | Arsenic | As6.00 (10) |

Iron | Fe6.00 (33) | ||

Carbon | C16.00 (21) | ||

Table 4: AAS analysis Results Before Adsorption

Sample | Arsenic mg/l | Cadmium mg/l | Chromium mg/l | Copper mg/l | Lead mg/l |

Sample A (Police college) | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.169 | 0.009 |

Sample B (Modaganari bypass) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.038 | 0.010 |

Sample C (Dala kwanan Osi) | 0.001 | 0.017 | 0.014 | 0.060 | 0.010 |

WHO standard | – | 0.003 | 0.050 | 1.500 | 0.010 |

The heavy metal Cd is a toxic non-essential transition metal that poses a health risk for both humans and animals, its exposure is known to have adverse effects on the kidney, liver, bones and cardio-pulmonary system, but the kidney is the critical organ, where chronic exposure to Cd often causes renal dysfunction [3,49]. Chromium (Cr), Copper (Cu) and lead (Pb) are known to cause cancer, gastrointestinal disorder, poor mental development respectively was found at maximum concentrations of 0.014mg/l, 0.169mg/l and 0.012mg/l respectively as against the maximum acceptable benchmark of 0.050mg/l, 1.00mg/l and 0.010mg/l respectively for Cr, Cu and Pb thereby indicating that all the three metals existed below the maximum permitted in all the three (3) borehole water sample. However, Cd which is known to be toxic to the kidney was the only heavy metal which was found to be existing at a concentration higher than that permitted for portable drinking water and thus if not significantly reduced in the water, it may pose a great danger to the consumer. Table 5 shows the AAS analysis after adsorption.

Table 5: AAS Analysis Result After Adsorption

| Dosage (g) | Arsenic (mg/l) | Cadmium (mg/l) | Chromium (mg/l) | Copper (mg/l) | Lead (mg/l) |

Sample A (Police college) | 1.0 ZnO/DTL | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

1.0 NI/DTL | 0.000 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.011 | 0.030 | |

Sample B (Modaganari byepass) | 1.0 ZnO/DTL | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.020 | 0.000 |

1.0 NI/DTL | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.017 | 0.013 | 0.002 | |

Sample C (Dala Kwanan Osi) | 1.0 ZnO/DTL | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.005 | 0.007 | 0.035 |

1.0 NI/DTL | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.007 | 0.017 | 0.090 | |

WHO standard | – | 0.003 | 0.050 | 1.500 | 0.010 |

The water samples A, B and C, is have shown a significant change of heavy metals based on the AAS result hence, Ar is completely removed from the water samples as a result. Cd which is queried has been removed significantly in Samples A, B and C with the most efficient adsorbent being ZnO/DTLAC further confirming that adsorbents impregnation improves the efficiency of the adsorbent, this finding agrees with other studies [50-52]. In sample C, which was initially harboring the highest concentration of Cd, it can be observed that the concentration is within the maximum permitted limits of 0.003 mg/l from Table 5.

Moreover, Cr, Cu and Pb has shown significant reduction in concentration where Cu and Pb were completely removed from water sample A by using the ZnO/DTLAC adsorbent. Cr and Pb were also completely removed from water sample B respectively. Also, Cr, Cu and Pb has also been significantly removed in sample C by the ZnO/DTLAC adsorbent. From Table 5, Cd was removed completely using impregnated adsorbent and reduced significantly by the application of non-impregnated adsorbent.

3.6 Adsorption isotherm study

The description of the ZnO/DTLAC adsorbent, was studied for the adsorption behavior using adsorption isotherm models where the adsorption capacity is explained by the models. The Langmuir is formulated as follows [53]:

$$q_e = \frac{q_m K_L C_e}{1 + K_L C_e} \tag{1}

$$

where, qe is the equilibrium adsorption capacity (mg/g), qm and KL are the maximum adsorption capacity to form a complete monolayer on the surface (mg/g), and the Langmuir constant related to the energy of adsorption (bonding energy of sorption in (L/g), respectively. The linearized form of Langmuir equation is:

$$\frac{C_e}{q_e} = \frac{1}{q_m K_L} + \frac{C_e}{q_m} \tag{2}$$

The dimensionless characteristic of Langmuir isotherm referring to the separation factor (RL) is useful in predicting the adsorption efficiency of the adsorption process. It is an indicator of Langmuir isotherm suitability as either unfavorable (RL > 1), linear (RL = 1), favorable (0 < RL< 1), or irreversible (RL = 0); RL can be express as:

$$RL = \frac{1}{1 + K_L C_0} \tag{3}$$

where Co is the highest initial concentration of the adsorbate (mg/L), and KL (L/mg) is the Langmuir constant. The Freundlich model is defined as:

$$q_e = K_f C_e^{1/n} \tag{4}$$

where Kf and 1/n are the Freundlich constants related to sorption capacity and sorption intensity, respectively. The linearized form of equation 1 can be obtained by taking logarithms on both sides:

$$\log q_e = \log K_f + \frac{1}{n} \log C_e \tag{5}$$

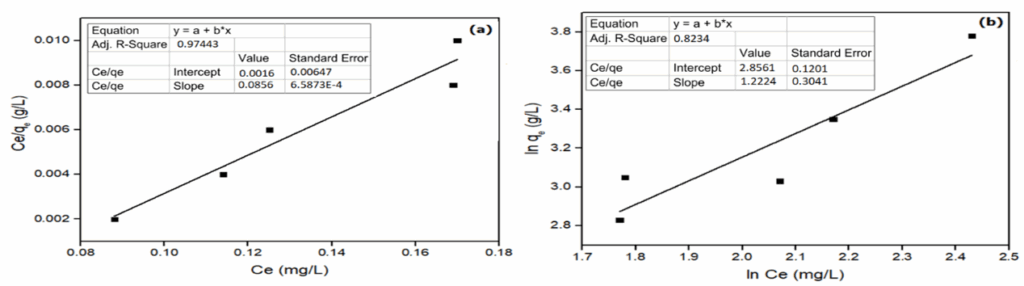

The applicability of an isotherm may be determined by the coefficient of determination (R2) [54] thus, the R2 value for adsorbent was found to be high in the Langmuir isotherm (0.9684) while that of Freundlich isotherm showed lower R2 (0.8479). Previous similar study can be found in the literature [55].

A dimensionless characteristic of Langmuir isotherm termed as the separation factor (RL) [50] is useful to predicts the adsorption efficiency of the adsorption process and shows the suitability of Langmuir isotherm as unfavorable (RL>1), linear (RL=1), favorable (0 < RL< 1) or irreversible (RL=0) [47]. Moreover, the Langmuir isotherm suitability was indicated by the favorable separation factor (RL) values gotten as 0.27. The heterogeneity factor (1/n) describing the adsorption capacity by Freundlich isotherm, and its value becomes more heterogeneous as it gets farther to one with the range of favorable adsorption as 1 < n < 10 [56-57].

In this study, the heterogeneity factor is 0.8180 which is not favorable. Therefore, the Langmuir isotherm supersedes the characteristics shown by the Freundlich isotherm hence it is more suitable to explicate the correlation of experimental results, similar work has been reported earlier [54,56,58]. Figure 5 shows the plot of (a) Langmuir Isotherm (b)Freundlich isotherm.

The Langmuir assumptions stated that at maximum adsorption, only a monolayer of adsorbed material is formed. Also, the molecules of adsorbate do not deposit on each other while the adsorption sites were identical. Secondly, under constant temperature, the adsorbed molecules do not interact. Thirdly, there are equal adsorption sites, and the surface of the adsorbent was uniform. Fourthly, the adsorption occurs through the same mechanism. By implication, these assumptions are applicable to the ZnO/DTLAC adsorbent, this finding agrees with the previous work [57].

4. Conclusion

The adsorption capacity of the activated carbon metal oxide impregnated (ZnO/DTLAC) and non-impregnated (NIDTLAC) adsorbents were studied, and the adsorbents were able to remove the heavy metals from three water samples to the required consumable standard. The micrograph by SEM showed that the surface structures are porous, with distributed pores over the carbonaceous matrix, while EDXRF showed the chemical composition of the adsorbent indicating the formation of nanocomposites and the loss on ignition value of the depicts high carbonaceous matter. The absorption band at 1578 cm-1 due to aromatic group (C-C), indicated the formation of carbonaceous in composite. XRD spectra of the showed a highly amorphous nature in absence of any of the heavy metals and the activated carbon pattern showed an amorphous halo centered at 2θ = 23O, which refers to the reflection of the plane (002), a common feature of non-crystalline structures such as activated carbon. The adsorbents developed are suitable for the decontamination of heavy metals from borehole water in some areas of Maiduguri, Nigeria.

- T. Rasheed, S. Sha, M. Bilal, T. Hussain, F. Sher, and K. Rizwan, “Surfactants-based remediation as an effective approach for removal of environmental pollutants — A review,” Journal of Molecular Liquids, vol. 318, pp. 1–15, 2020.

- A. A. Siyal et al., “A Review on geopolymers as emerging materials for the adsorption of heavy metals and dyes,” . Journal of Environmental Management., vol. 224, pp. 327-no. 339, 2018.

- G. Genchi, M. S. Sinicropi, G. Lauria, and A. Carocci, “The effects of cadmium toxicity,” International Journal of Environment Resource and Public Health, vol. 17, no. 3782, pp. 1–24, 2020.

- W. P. Cheng, J. G. Yang, and M. Y. He, “Evaluation of crystalline structure and SO2 removal capacity of a series of MgAlFeCu mixed oxides as sulfur transfer catalysts,” Catalysis Communications, vol. 10, no. 6, pp. 784–787, 2009.

- A. Jain, R. Balasubramanian, and M. P. Srinivasan, “Hydrothermal conversion of biomass waste to activated carbon with high porosity: A review,” Chemical Engineering Journal, vol. 283, pp. 789–805, 2016.

- B. Ni, Q. Huang, C. Wang, T. Ni, J. Sun, and W. Wei, “Competitive adsorption of heavy metals in aqueous solution onto biochar derived from anaerobically digested sludge,” Chemosphere, vol. 219, pp. 351-357, 2019.

- R. Chakraborty, A. Asthana, A. K. Singh, and B. Jain, “Adsorption of heavy metal ions by various low-cost adsorbents: A review,” International Journal of Environmental Analytical Chemistry, pp. 1–38, 2020.

- M. T. A. Shafiq, A.A. Alazba, “Removal of heavy metals from wastewater using Date Palm as a biosorbent: A Comparative Review,” Sains Malaysiana, vol. 47, no. 1, pp. 35–49, 2018.

- Z. Z. Ismail, “Kinetic study for phosphate removal from water by recycled date-palm wastes as agricultural by-products,” International Journal of Environment., pp. 37–41, 2012.

- M. Abdullahi, S. A. Yahaya, M. K. Sanusi, B. E. Sambo, S. B. Abba “The potentials of esterblishing date palm plantation in sudano sahelian region of Nigeria.” Conference: Farm Management Association of Nigeria (FAMAN) At: General Studies Auditorium, Federal University Dutse, Jigawa State Nigeria. 2015.

- M. Kamaraj, N. R. Srinivasan, G. Assefa, A. T. Adugna, and M. Kebede, “Facile development of sunlit ZnO nanoparticles-activated carbon hybrid from pernicious weed as an operative nano-adsorbent for removal of methylene blue and chromium from aqueous solution: Extended application in tannery industrial wastewater,” Environmental Technology and Innovation, vol. 17, pp. 10–40, 2020.

- S. Kiman, G. W. Azlina, C.Thomas, and R. Umer, “Carbonaceous materials modified catalysts for simultaneous SO2/NO x removal from flue gas: A review,” Catalysis Review, vol. 61, no. 1, pp. 1–28, 2018.

- M. A. Naeem et al., “Batch and column scale removal of cadmium from water using raw and acid activated wheat straw biochar,” Water (Switzerland), vol. 11, no. 7, pp. 1–17, 2019.

- R. Kumar and J. Chawla, “Removal of Cadmium Ion from water/wastewater by nano-metal Oxides: A review,” Water Quality Exposure and Health, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 215–226, 2014.

- S. Alhan, M. Nehra, N. Dilbaghi, N. K. Singhal, K. H. Kim, and S. Kumar, “Potential use of ZnO@activated carbon nanocomposites for the adsorptive removal of Cd2+ ions in aqueous solutions,” Environmental Resource, vol. 173, pp. 411–418, 2019.

- K. Pyrzynska, “Removal of cadmium from wastewaters with low-cost adsorbents,” Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 1–40, 2019.

- W. M. H. Wan Ibrahim, M. H. Mohamad Amini, N. S. Sulaiman, and W. R. A. Kadir, “Powdered activated carbon prepared from Leucaena leucocephala biomass for cadmium removal in water purification process,” Arab Journal of Basic Appllied Science, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 30–40, 2019.

- M. R. Awual, “A facile composite material for enhanced cadmium(II) ion capturing from wastewater,” Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 1–11, 2019.

- K. Silas, W. A. W. Ghani, T. S. Y. Choong, R. Umer , “Breakthrough studies of Co3O4 supported activated carbon monolith for simultaneous SO2/NOx removal from flue gas,” Fuel Processing Technolology, vol. 180, pp. 155–165, 2018.

- T. Tay, S. Ucar, S. Karagöz, “Preparation and characterization of activated carbon from waste biomass,” . Journal of Hazardous Materials, vol. 165, no. 1–3, pp. 481–485, 2009.

- M. Zbair, Z. Anfar, H. Ait Ahsaine, N. El Alem, and M. Ezahri, “Acridine orange adsorption by zinc oxide/almond shell activated carbon composite: Operational factors, mechanism and performance optimization using central composite design and surface modeling,” Journal of Environmental Management, vol. 206, pp. 383–397, 2018.

- M. A. Tariq et al., “Effective sequestration of Cr (VI) from wastewater using nanocomposite of ZnO with cotton stalks biochar: modeling, kinetics, and reusability,” Environmental Science and Pollution Research, vol. 27, pp. 33821–33834, 2020.

- J. Peternela, M. F. Silva, M. F. Vieira, R. Bergamasco, and A. M. S. Vieira, “Synthesis and impregnation of copper oxide nanoparticles on activated carbon through green synthesis for water pollutant removal,” Research, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 1–11, 2018.

- A. M. Awwad, M. W. Amer, and M. M. Al-aqarbeh, “TiO2-kaolinite nanocomposite prepared from the Jordanian Kaolin clay: Adsorption and thermodynamics of Pb(II) and Cd(II) ions in aqueous solution,” Chemistry International , vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 168–178, 2020.

- C. Ma et al., “Honeycomb tubular biochar from fargesia leaves as an effective adsorbent for tetracyclines pollutants,” Journal of The Taiwan Institute Of Chemical Engineers, vol. 91, pp. 299–308, 2018.

- S. Ilyas, D. Tahir, Suarni, B. Abdullah, and S. Fatimah, “Structural and bonding properties of honeycomb structure of composite nanoparticles Fe3O4 and activated carbon,” Journal Of Physics: Conference Series, vol. 1317, no. 1, pp. 1–8, 2019.

- G. B. Adebayo, F. A. Adekola, H. I. Adegoke, S. Fausiyat, and J. Wasiu, “Synthesis and characterization of goethite, activated carbon and their composite,” Journal of Chemical Technology And Metallurgy, vol. 55, no. 5, pp. 1068–1077, 2020.

- O. O. Olubajo, I. Y. Makarfi, and O. A. Odey, “Prediction of loss on ignition of ternary cement containing coal bottom ash and imestone using central composite design,” Path of Science, vol. 5, no. 8, pp. 2010–2019, 2019.

- B. Abdullah, S. Ilyas, and D. Tahir, “Nanocomposites Fe/Activated Carbon/PVA for microwave absorber: Synthesis and characterization,” Journal of Nanomaterials., vol. 2018, pp. 1–7, 2018.

- A. Kumar and P. Lingfa, “Sodium bentonite and kaolin clays: Comparative study on their FT-IR, XRF, and XRD,” Materials Today: Proceedings, vol. 22, pp. 737–742, 2020.

- D. Tahir, S. Liong, and F. Bakri, “Molecular and structural properties of polymer composites filled with activated charcoal particles,” AIP Conference Proceedings, vol. 1719, pp. 1–5, 2016.

- E. Carpio, P. Zúñiga, S. Ponce, J. Solis, J. Rodriguez, and W. Estrada, “Photocatalytic degradation of phenol using TiO2 nanocrystals supported on activated carbon,” Journal of Molecular Catalysis A: Chemical, vol. 228, no. 1–2, pp. 293–298, 2005.

- V. K. Gupta, S. Agarwal, R. Ahmad, A. Mirza, and J. Mittal, “Sequestration of toxic congo red dye from aqueous solution using ecofriendly guar gum/activated carbon nanocomposite,” . International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, vol. 158, pp. 1–33, 2020.

- S. Sahu, S. Pahi, J. K. Sahu, U. K. Sahu, and R. K. Patel, “Kendu (Diospyros melanoxylon Roxb) fruit peel activated carbon — an efficient bioadsorbent for methylene blue dye: equilibrium, kinetic, and thermodynamic study,” Environmental Science and Pollution Research, vol. 27, pp. 1–14, 2020.

- B. K. Saikia, R. K. Boruah, and P. K. Gogoi, “XRD and FT–IR investigations of sub-bituminous Assam coals,” Material Science, vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 421–426, 2007.

- O. O. Sonibare, T. Haeger, and S. F. Foley, “Structural characterization of Nigerian coals by X-ray diffraction, Raman and FTIR spectroscopy,” Energy, vol. 35, no. 12, pp. 5347–5353, 2010.

- S. Lin et al., “A study on the FTIR spectra of pre- and post-explosion coal dust to evaluate the effect of functional groups on dust explosion,” Process Safety and Environmental Protectio., vol. 130, pp. 48–56, 2019.

- S. Alshuiael, A. Mohammad, “Multivariate analysis for FTIR in understanding treatment of used cooking oil using activated carbon prepared from olive stone,” PLoS One, vol. 15, no. 5, pp. 1–25, 2020.

- A. H. Wazir, I. U. Wazir, and A. M. Wazir, “Environmental effects preparation and characterization of rice husk based physical activated carbon,” Energy Sources, Part A: Recovery, Utilization, And Environmental Effects, pp. 1–11, 2020.

- P. Jujur, M. Nur, M. Asy, and H. Nur, “SEM, XRD and FTIR analyses of both ultrasonic and heat generated activated carbon black microstructures,” Heliyon, vol. 6, pp. 1–16, 2020.

- D. Gandhi, R. Bandyopadhyay, and S. Parikh, “Structural and composition enhancement of Indian Kachchh kaolin clay: characterisation and application as low-cost catalyst” Indian Chemical Engineer, pp. 1–11, 2020.

- A. J. Bora and R. K. Dutta, “Removal of metals (Pb, Cd, Cu, Cr, Ni, and Co) from drinking water by oxidation-coagulation-absorption at optimized pH,” Journal of Water Process Engineering, vol. 31, pp. 1–9, 2019.

- S. C. Rodrigues, M. C. Silva, J. A. Torres, and M. L. Bianchi, “Use of magnetic activated carbon in a solid phase extraction procedure for analysis of 2, 4-dichlorophenol in water samples,” Water Air Soil Pollution, vol. 231, no. 294, pp. 1–13, 2020.

- D. Propolsky, E. Romanovskaia, W. Kwapinski, and V. Romanovski, “Modified activated carbon for deironing of underground water,” Environmental Research, vol. 182, pp. 1–16, 2020.

- A. I. Osman, C. Farrell, A. H. Al-muhtaseb, H. John, and D. W. Rooney, “The production and application of carbon nanomaterials from high alkali silicate herbaceous biomass,” Scientific Reports, vol. 10, no. 2563, pp. 1–13, 2020.

- M. K. A. Mohammed, D. S. Ahmed, and M. R. Mohammad, “Studying antimicrobial activity of carbon nanotubes decorated with metal-doped ZnO hybrid materials,” Mater. Res. Express, vol. 6, no. 5, pp. 1–16, 2019.

- Q. Ain, M. U. Farooq, and M. I. Jalees, “Application of magnetic graphene oxide for water puri fication: Heavy metals removal and disinfection,” Journal of Water Process Engineering, vol. 33, pp. 1–14, 2020.

- C. F. Ramirez-gutierrez, R. Arias-niquepa, J. J. Prías-barragán, and M. E. Rodriguez-garcia, “Study and identification of contaminant phases in commercial activated carbons,” Journal Of Environmental Chemical Engineering, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 10-36, 2020.

- M. B. Arain, T. G. Kazi, J. A. Baig, and H. I. Afridi, “Co-exposure of arsenic and cadmium through drinking water and tobacco smoking: Risk assessment on kidney dysfunction,” Environmental Science Pollution Resource, vol. 22, pp. 350–357, 2015.

- S. S. Shah, T. Sharma, B. A. Dar, and R. K. Bamezai, “Adsorptive removal of methyl orange dye from aqueous solution using populous leaves: Insights from kinetics, thermodynamics and computational studies,” Enviromental Chemistry and Ecotoxicoly, vol. 3, pp. 172–181, 2021.

- M Vakili, H. M. Zwain, A. Mojiri, W. Wang, F. Gholami, Z. Gholami, A. S. Giwa, B. Wang, G. Cagnetta, B. Salamatinia, “Effective adsorption of reactive black 5 onto hybrid hexadecylamine impregnated chitosan-powdered activated carbon beads,” Water, vol. 12, no. 2242, pp. 1–14, 2020.

- K. Azam R. Raza, N. Shezad, M. Shabir, W. Yang, N. Ahmad, I. Shafiq, P. Akhter, A. M. Hussain, “Development of recoverable magnetic mesoporous carbon adsorbent for removal of methyl blue and methyl orange from wastewater,” Environmental Chemistry and Ecotoxicology, vol. 8, no. 5, pp. 1–20, 2020.

- S. Kiman, G. W. Azlina, C.Thomas, and R. Umer, “Monolith metal-oxide-supported catalysts: Sorbent for environmental application,” Catalyst, vol. 10, pp. 1–25, 2020.

- P. Ganguly, R. Sarkhel, and P. Das, “Synthesis of pyrolyzed biochar and its application for dye removal: Batch, kinetic and isotherm with linear and non-linear mathematical analysis,” Surfaces and Interfaces, vol. 20, pp. 1–16, 2020.

- V. P. Singh and R. Singhal, “Optimization of dye removal by diesel exhaust emission soot using response surface methodology,” Environmental Progress Sustainable Energy, pp. 1–11, 2020.

- E. E. Jasper, V. Olatunji, A. Jude, and C. Onwuka, “Nonlinear regression analysis of the sorption of crystal violet and methylene blue from aqueous solutions onto an agro ‑ waste derived activated carbon,” Applied Water Science, vol. 10, no. 6, pp. 1–11, 2020.

- S. Ullah et al., “Synthesis and characterization of mesoporous MOF UMCM-1 for CO2CH4 adsorption; An experimental, isotherm modeling and thermodynamic study,” Microporous Mesoporous Materials., vol. 294, pp. 1–44, 2019.

- J. Garc, “Biochar from agricultural by-products for the removal of lead and cadmium from drinking water,” Water, vol. 12, no. 2933, pp. 1–16, 2020.

- Kiman Silas, Aliyu B. Ngulde, Habiba D. Mohammed, “Experimental Study of the Short-Circuit Current Performance of \(10\,\mathrm{kA_{R.M.S}}\) and \(20\,\mathrm{kA_{R.M.S}}\) Polymer Surge Arrester”, Journal of Engineering Research and Sciences, vol. 4, no. 12, pp. 15–24, 2025. doi: 10.55708/js0412002